Trigger warning: This story contains themes of suicide and is based on true events. To protect privacy, names and locations have been altered.

It was another perfect spring Sunday in Perth. The sun had just begun its slow crawl over the horizon as John drove east along Reid Highway toward the station. The early light slashed across the sky, a streak of gold over the Perth Hills—a view some might call serene. To John, it was just another distraction as he squinted against the glare, fighting off the dregs of sleep.

His mind wandered: the shift ahead, the exam he had to cram for, the plans for tomorrow—a quiet day with his wife and their two-year-old daughter. They’d just bought a trampoline. He could already picture her wide-eyed excitement, the way she’d shriek with laughter as she bounced for the first time. A simple thing. But everything to him.

Two years into his five-year firefighter traineeship, John still felt pride every time he put on the uniform, even when its weight felt heavier some days. His father had worn it. His grandfather before him. Firefighting wasn’t just a career—it was in his blood, part of his DNA.

An hour into his shift, halfway through his coffee, highlighter in one hand, exam notes in the other, the pager shrieked. First job of the day. A smoke alarm in a townhouse, ten minutes away. Probably just another cheap lithium battery fire. Routine.

But nothing ever stays routine for long.

John and the crew suited up, piled into the Toyota Landcruiser and the Urban Pumper, and rolled out toward Bassendean. The familiar rumble of the engine beneath him. The quiet tension of the ride. He pushed thoughts of his family aside. There was work to do.

At the scene, they moved fast, falling into their practiced rhythm. No one answered when they called out. The door had to come down.

John stepped inside first.

The townhouse was still, thick with the sting of smoke. His boots tapped against the floor as he scanned the space—a neat dining table, framed photos of a smiling man. Fit. Sandy-haired. Brown eyes bright with life. Beside him, a little girl, no older than eight, beamed up at the camera. Same brown eyes. Same sandy hair. The connection between them was undeniable.

And next to the photos, a letter.

It was titled, To my Amelia.

John’s pulse spiked. A slow, creeping unease coiled in his stomach.

“This isn’t a battery fire,” he murmured.

“Call it in,” his colleague responded.

The team split up, clearing the townhouse room by room. Then they reached the bathroom. The door was locked.

A quick breach. Smoke rushed out. The air thickened, clawing at his lungs. Then—

They found him.

The man from the photo. Only now, he was something else entirely.

John had seen death before—car accidents, fires, bodies mangled by trauma—but this was different.

The man had built a teepee-like structure from charcoal briquettes, sealing himself inside to let the fumes take him. It had worked. But what he hadn’t accounted for was the heat. As he lost consciousness, his body had slumped over the coals. The fumes had done their job. The fire had done the rest.

Now, he was barely recognisable. His skin, warped and melted, clung to his bones like candle wax left too close to a flame.

John froze. A heartbeat. Then another.

The photographs flashed in his mind—the beaming man, the little girl who shared his eyes. Amelia.

The air was heavy, suffocating.

Then, just as quickly as it came, the moment passed.

Another call. Another shift. Another tragedy absorbed into the rhythm of the job.

Just another day as a first responder.

It’s the conversation that doesn’t happen nearly enough

Some moments stay with you forever.

For John, it was that townhouse. The locked bathroom. The letter titled To my Amelia.

For others, it’s a call that never came. A friend they thought was fine. A loved one who was almost okay—until they weren’t.

Suicide, depression, and anxiety aren’t just abstract issues. They touch lives in ways most of us don’t realise until it’s too late.

Welcome to another entry of The Integrated Masculine Man. Today, we’re diving into a topic that is often uncomfortable but absolutely necessary—mental health. While I’ve personally experienced feelings of anxiety and depression, I consider myself fortunate not to have been diagnosed with these conditions. However, I have friends, family, and coworkers who haven’t been as lucky. Their struggles fuel my passion for mental health awareness and breaking the silence around these issues.

First, a disclaimer: I’m not a mental health professional. I merely write subjective to my own lived experiences. If you are concerned about someone’s immediate welfare please contact your local emergency services immediately. If you are experiencing thoughts of or practicing self-harm, suicide or any other violence—please reach out to emergency services or a crisis helpline. I will link some great resources at the end of this post.

In this entry, we’ll explore three major mental health challenges—depression, anxiety, and suicidality. You’ll learn how to recognise when someone is struggling, how to start that tough conversation, and, most importantly, what you can do to support those around you. I’ll also highlight a movement making a real impact in the mental health space.

Because talking about it could be the difference between life and death.

The age of disconnection

Reports from Harvard University indicate that 1 in 2 people will experience a mental health disorder at some point in their life. Despite this statistic, there remains a significant stigma around discussing mental health, particularly among men. This stigma often stems from societal expectations and traditional notions of masculinity, which discourage men from expressing vulnerability or seeking help. The result is a culture where many men suffer in silence, feeling isolated and unsupported.

In the peak of our current age—the Age of Information—we have never been more connected. Social media, instant messaging, and other digital platforms allow us to communicate with anyone, anywhere, at any time. Yet, when it comes to mental health, we’ve never been so disconnected. The paradox is striking: while we can share our lives with the world in an instant, many still feel unable to share their struggles with those closest to them. This disconnection is particularly pronounced in the realm of mental health, where fear of judgment and misunderstanding often prevents open conversations.

When it comes to chronic mental health illnesses, roughly 1 in 20 adults will experience a serious mental health illness each year. Serious mental illnesses include conditions like major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, which can significantly impact daily functioning and quality of life. For me personally—this includes not just one, but both of my parents.

Breaking down these barriers around these stigmas requires a cultural shift towards greater acceptance and understanding of mental health issues. By fostering open dialogues and challenging outdated stereotypes, we can create a more supportive environment where everyone feels empowered to seek help and support.

How ya going mate… but not really

In Australian culture, the greeting “How ya going, mate?” is a common and friendly way to acknowledge someone in passing. It’s used between friends, coworkers, or even strangers as a casual way to say hello. This phrase, while warm and approachable, is typically not intended to elicit a detailed response about one’s well-being. Instead, it’s more of a social nicety, a way to maintain a friendly atmosphere without delving into personal matters.

Despite its friendly tone, “How ya going, mate?” doesn’t create an inviting space for someone to truly open up about their feelings, especially if they are struggling with poor mental health. The expectation is usually a brief, positive response like “Good, thanks” or “Not bad,” rather than an honest account of one’s emotional state. This can be particularly challenging for individuals experiencing depression or anxiety, as they might feel the need to mask their true feelings to conform to social norms. While the greeting fosters a sense of camaraderie, it also highlights the gap between casual interactions and meaningful conversations about mental health.

The new age great depression

The Great Depression of 1929 was an economic catastrophe—banks collapsed, unemployment skyrocketed, and millions lost their homes. It reshaped financial policies and left a permanent mark on society, proving how fragile economic systems can be.

Fast forward to today, and we’re in the midst of a different kind of depression—one that affects the mind instead of the markets. Despite our technological progress, global wealth, and medical advancements, mental health issues, particularly depression, are on the rise. Right now, around 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression—far more than those affected by the economic Great Depression when the world’s population was just 2 billion.

The irony is hard to ignore: life is, in many ways, easier than ever, yet more people than ever are struggling with their mental well-being. This modern-day “Great Depression” isn’t about financial collapse—it’s about emotional exhaustion, social disconnection, and the overwhelming pressures of modern life.

Just as the economic Great Depression forced systemic change, today’s mental health crisis demands a shift in how we approach well-being. We need better awareness, more accessible care, and a society that treats mental health with the same urgency as physical health.

The black dog

So, what exactly is depression? Everyone feels down sometimes, but depression is more than just a rough patch. It lingers, deepens, and affects every part of life.

Imagine waking up with a weight on your chest so heavy that even getting out of bed feels impossible. Things that once brought joy now feel meaningless. Some people withdraw, isolating themselves from loved ones. Others experience changes in appetite, sleep patterns, and energy levels—either too much or too little of everything. Concentration becomes difficult, decisions feel overwhelming, and even the smallest tasks seem exhausting.

Depression isn’t just “feeling sad”—it’s a medical condition that affects the brain, body, and daily life. And it’s more common than many realise.

What to look for – depression

Recognising depression means looking beyond emotions. It can show up in different ways:

Cognitive – Difficulty focusing, negative self-talk, indecisiveness.

Emotional – Persistent sadness, hopelessness, irritability, or guilt.

Physical – Fatigue, appetite or sleep changes, lack of energy.

Behavioural – Social withdrawal, loss of interest in hobbies, low motivation.

The good news? Help is available. Depression is not a personal failure—it’s an illness that can be treated. If you or someone you know is struggling, reaching out to a friend, family member, or professional can make all the difference. You don’t have to face it alone.

Spiraling into anxiety

Everyone experiences anxiety at some point—it’s a natural response to stress. But when anxious feelings linger, appear without reason, or start interfering with daily life, it may be a sign of an anxiety disorder.

Anxiety is one of the most widespread mental health issues today, affecting millions worldwide. In 2019, the World Health Organization reported that 301 million people were living with an anxiety disorder, making it the most common mental health condition globally. These disorders take many forms—generalised anxiety, panic disorder, and social anxiety, to name a few—each bringing its own set of challenges.

In Australia alone, anxiety affects around 3.4 million people annually, with young adults particularly impacted. Nearly 40% of Australians aged 16-24 experience a mental health disorder each year, with anxiety at the forefront. But this isn’t just an Australian issue—it’s a global trend. Events like the COVID-19 pandemic, economic instability, and social unrest have only intensified stress levels, pushing anxiety rates even higher.

Despite growing awareness, many people still hesitate to seek help. Stigma, lack of access to care, and the belief that their struggles aren’t “serious enough” stop them from reaching out. But that narrative is changing. Initiatives like The Shaka Project are helping break the silence, encouraging open conversations and reducing the stigma around mental health.

As modern life becomes more demanding, prioritising mental well-being is more important than ever. By fostering supportive environments and making mental health care accessible, we can help more people manage anxiety before it takes over their lives.

Recognising anxiety

Anxiety can show up in different ways, affecting both the mind and body. Here’s what to look for:

Cognitive – Racing thoughts, trouble concentrating, excessive worrying, difficulty sleeping.

Emotional – Constant nervousness, restlessness, or a sense of impending doom.

Physical – Increased heart rate, rapid breathing, sweating, trembling, fatigue, digestive issues.

Behavioural – Avoiding situations that trigger anxiety, withdrawing from social activities.

These symptoms vary in intensity, often peaking in high-stress situations. If anxiety starts to take control, small strategies can help—breathwork, muscle relaxation, or setting achievable goals to slowly face anxious situations. But if anxiety feels overwhelming, speaking with a professional can make all the difference.

Anxiety or panic attacks

The first time I saw someone have a panic attack, I had no idea what was happening. We were skiing when she suddenly froze—breathing fast, panicked, unable to move. At the time, I didn’t know how to help. Looking back, I wish I had the knowledge I do now to support her properly.

If you or someone you’re with has a panic attack, here’s what to do:If you experience or witness someone having a panic attack, follow these steps:

- Stop and find a quiet space – Sit or lie down to help reduce overstimulation.

- Reassure them – Stay calm, let them know they’re safe.

- Guide their breathing – Try this simple technique:

- Inhale through the nose for 4 seconds

- Hold for 4 seconds

- Exhale slowly through the mouth for 4 seconds

- Repeat until breathing steadies and symptoms ease

- If symptoms persist, seek medical help.

Understanding how to handle anxiety and panic attacks can make a world of difference. By staying calm, patient, and informed, we can help those struggling feel safe and supported.

Mental health education isn’t just about awareness—it’s about action. The more we learn, the more we can build a compassionate and understanding community.

Understanding suicidality

Sometimes, life throws us into situations that feel impossible to handle. When this happens, some people might think about suicide but not act on those thoughts, while others might see it as their only way to escape unbearable pain. The reasons behind these thoughts are complex and different for everyone.

When someone reaches crisis mode, it’s beyond early intervention. This is when their mindset shifts from “I can’t do anything right” to “the world would be better off without me.“

There are many factors that can lead to suicidality:

- Individual factors: Things like substance abuse, chronic pain, impulsive tendencies, and mental health disorders.

- Relationship factors: Issues like domestic abuse, a family history of suicide, or social isolation.

- Community factors: Discrimination, violence, or lack of access to proper mental health care.

- Societal factors: Stigmas around mental health or easy access to methods of suicide.

The four stages of suicidal ideation

Suicidal thoughts usually progress through stages:

- Acknowledge: Realising that suicide is a possible response to overwhelming circumstances. The person starts to see it as a potential, though tragic, option.

- Accept: Accepting that suicide could be an acceptable solution under certain conditions. This acceptance can linger even if they don’t act on these thoughts right away.

- Anticipate: Starting to anticipate that suicide might become inevitable. This stage often involves planning and preparing for a potential attempt.

- Action: Taking action, which can be either a sudden, impulsive decision or a more organised and deliberate plan.

Understanding these stages can help us identify warning signs and intervene early. If you or someone you know is struggling, seek professional help immediately.

What to look for – suicidality

Spotting if someone is suicidal can be tough, but here are some signs to watch for:

Verbal Cues: Talking about feeling hopeless, worthless, or like a burden. Expressing a desire to die or saying they have no reason to live.

Behavioural Changes: Withdrawing from social activities, giving away prized possessions, or making arrangements for their affairs.

Mood Swings: Sudden shifts from deep sadness to calmness, which might indicate they’ve made a decision to attempt suicide.

Risky Behaviour: Engaging in reckless or self-destructive activities, like increased substance use or unsafe driving.

Physical Symptoms: Changes in sleep patterns, appetite, or personal appearance. They might sleep too much or too little, eat significantly more or less, or neglect their hygiene.

If you notice these signs in someone, take them seriously and reach out for help. Encourage them to speak with a mental health professional and offer your support. In urgent situations, contact emergency services or a crisis hotline. In Australia, dial 000.

How you can start the conversation

Approaching a conversation about mental health can be delicate, but it’s important to show care and support. Here are some tips:

Choose the right time and place: Find a quiet, private setting where you can talk without interruptions. This helps create a safe and comfortable environment for the person to open up.

Make it relevant to the situation and the person: Tailor your approach based on what you know about the person’s current circumstances. Mention specific observations or concerns that prompted you to start the conversation.

Explore options for support: Discuss different types of support available, such as therapy, support groups, or talking to a trusted friend or family member. Offer to help them find resources or accompany them to an appointment if they feel comfortable.

Focus on the factors that influence mental health and well self: Talk about lifestyle factors like sleep, diet, exercise, and social connections. Encourage small, manageable changes that can have a positive impact on their mental health.

Actively listen and be present: Give your full attention, make eye contact, and show that you are genuinely interested in what they have to say. Avoid interrupting or offering solutions right away; just listen.

Ask open questions: Use questions that encourage the person to share more about their feelings and experiences. Examples include “How have you been feeling lately?” or “Can you tell me more about what’s been going on?”

Help the person develop goals and actions: Work together to set small, achievable goals that can help improve their mental health. This can provide a sense of direction and purpose, making the situation feel more manageable.

Explore what the person has done in the past to help themselves: Discuss strategies or activities that have helped them cope in the past. This can provide insight into what might work for them now and reinforce their ability to manage their mental health.

Don’t be afraid of silence; it gives people time to think: Allow pauses in the conversation to give the person time to process their thoughts and feelings. Silence can be powerful and shows that you are patient and willing to listen.

Approach: calm, present, non-judgmental, safe, interested, genuine, careful, sensitive and trustworthy: Your demeanor can significantly impact how comfortable the person feels opening up to you.

Be prepared for serious disclosures: If someone tells you they are considering or planning suicide, take it seriously. Stay with them, listen without judgment, and encourage them to seek immediate professional help. In urgent situations, contact emergency services or a crisis hotline.

By approaching the conversation with empathy and understanding, you can help create a safe space for them to open up and seek the help they need.

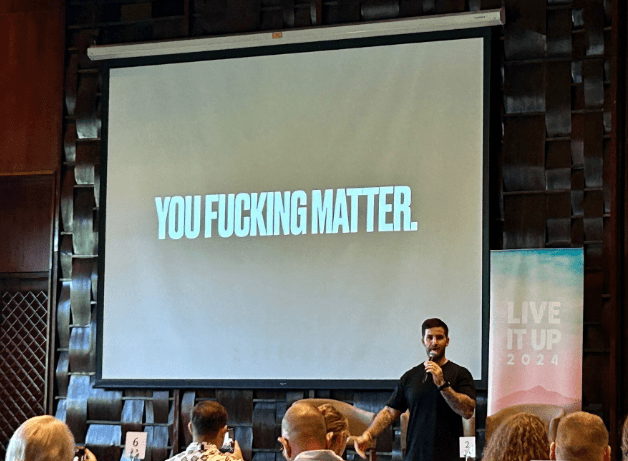

Community movement: The Shaka Project

The Shaka Project was founded by Sean Phillip in 2019 with a single goal in mind: “Igniting the conversation.“

What started as a passion project was deeply personal—born from Sean’s own mental health journey, which began at the age of 15 and continues to be part of his life today.

Depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder—whatever the challenge, mental health issues affect millions of Australians. For Sean, these struggles were deeply personal. Over the past 16 years, he has battled suicidal ideation, self-harm, and even suicide attempts.

But it was this very journey that fueled his mission to create The Shaka Project.

When Sean first experienced poor mental health, he was struck by the stigma surrounding men speaking up. He knew he needed help, yet fear kept him silent—a reality faced by far too many men. That fear, that silence, was exactly what he set out to change.

At first, he had no idea how to break the stigma. But he knew he had to try.

Since 2019, The Shaka Project has grown from a small idea into a nationally recognised charity. They’ve presented to over 10,000 students, athletes, and employees across Australia and sold nearly 45,000 conversation starters—merchandise designed to spark discussions about mental health.

The message is simple: The statistics don’t lie. Just six weeks into 2025, the world has already lost over 100,000 people to suicide. In Australia alone, 9 people die by suicide every day—7 of them are men. It’s time to talk. It’s time to normalise checking in on our mates.

It’s time to tell the people we love that we love them.

I had the privilege of seeing The Shaka Project in action last year when Sean came to my workplace. He spoke to two groups—nearly two hundred of our team members, partners, and leadership. Watching him share his story and witnessing the impact it had on those in the room was invaluable.

One of the most powerful moments in Sean’s story was when he recalled his father sitting him and his brother down—not just to tell them he was battling depression, but to show them that he was doing something about it.

At the time, Sean didn’t fully grasp the significance of that moment. But years later, when depression came knocking on his own door, that memory gave him the strength to seek help.

That one conversation changed everything.

And that’s how we break the cycle. That’s how we shatter the stigma—by talking about it, by showing the next generation that asking for help isn’t weakness. It’s strength.

Everyone deserves kindness

Take a moment to think about the people closest to you. If your life hasn’t been touched by suicide in some way, count your lucky stars. But even if that’s the case, I’d wager you know someone—a friend, a family member, a coworker—who has struggled with their mental health. Don’t wait until it’s too late to reach out.

If this post has resonated with you, I ask just one thing:

Think about that person you thought of earlier—the one who hasn’t quite seemed themselves at times. Reach out to them. You don’t have to ask how they’re doing, and you don’t have to bring up mental health. Just let them know you were thinking about them.

- It might be awkward. And that’s okay.

- It might spark a conversation—maybe brief, maybe deep—but either way, all you’ll have given up is a little bit of time.

And here’s the thing: that one message could save a life. Sometimes, all someone needs is to know they’re on someone’s mind. That they matter. That they belong.

This entry of The Integrated Masculine Man was a tough one to write—one I had to step away from and return to because of the memories it stirred. Thank you for taking the time to read it. You are appreciated, and you are loved.

–TIMM

Mental Health Support Services

Lifeline: 13 11 14

1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732

13 YARN: 13 92 76

Suicide Callback: 1300 659 467

Kids Helpline: 1800 55 1800

Head To Health: 1800 595 212

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

MensLine Australia: 1300 78 99 78

TalkSpace: https://www.talkspace.com/

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, you should call 000, visit your nearest hospital emergency department, or use any of these crisis helplines.

Leave a comment